The Delaware Aqueduct supplies nearly half of New York City’s drinking water. It provides approximately 600 million gallons of water to New Yorkers and people living in 70 other communities. Every day.

For decades, however, the aqueduct has been losing enormous amounts of water at two sites. By some estimates, nearly 15-35 million gallons of water are lost every day from this major pipeline. The breach in the pipeline was monitored from 1992 and in 2010, the city of New York announced a billion-dollar plan to repair the pipeline. The project is the largest repair project in New York City’s nearly 200-year-old water supply system. At its heart, the plan will build an enormous bypass around the leaking section near the Hudson River.

When such large pipelines start losing water, the problem becomes apparent very quickly. Homes in the region begin to flood, and the level of water in wells begins to rise. For instance, residents of Wawarsing, near the largest leak of the Delaware Aqueduct, were often pumping water out of their basements for weeks at a time.

While such breaches are a huge problem, they are not the only way in which cities, communities, and buildings lose water.

Most cities draw their water from distant watersheds. Mumbai, for instance, obtains its water from dams such as Bhatsa and Vaitarna in Thane. Water from these regions is extracted, treated, and pumped towards the city. Once it enters Mumbai, it enters a labyrinthine network of underground pipes before it reaches the ultimate consumer – in homes, offices, and industrial complexes. At each stage of transmission, water is lost from aging infrastructure, through rusted joints and worn-out pipes. Even internal plumbing in many buildings is prone to this problem.

However, this water is not usually measured, is unmonitored, and in most cases, no one is even aware of water being lost to a leak.

A World Bank-sponsored study released in 2007 found that more than a third of the water in one of Mumbai’s largest localities was leaking from its pipes. The municipality contested this figure. However, this is a problem that plagues many cities across the world. According to research published in 2015, nearly 50% of the water entering Italy’s national water distribution networks is lost to leakages.

Administrators respond to this challenge by restricting the supply of municipal water. Water is pumped at a lower pressure, for a smaller period of time, and obtaining new connections to the water network is made difficult or unaffordable. Researchers point out that for most large cities in India, it can be difficult to supply water at adequate pressure 24/7. For urban residents, municipal water is supplemented by pumping groundwater, through rainwater harvesting, reusing treated grey water, or by purchasing water in tankers. For nearly everyone in India, the water flowing from the tap throughout the day is an illusion created by a complex plumbing architecture of pumps and storage devices within their buildings.

Veena Srinivasan at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bangalore says that pushing water through a pipe intermittently and at varying pressures accelerates wear and tear. It speeds up the process of corrosion and places an additional strain on joints in the plumbing. Intermittent water supply also reduces the accuracy of mechanical flow meters. This adds an additional layer of ambiguity in tracking and monitoring water.

Water scarcity has social effects but there is an immediate, physical impact on the plumbing infrastructure as well. When some residents cannot access a sufficient amount of water or find it becoming unaffordable, they might create unauthorised connections by hacking into the city’s distribution network and diverting a small quantity towards their settlement. Such ‘social’ leaks add a great deal of uncertainty about water pressure and demand.

Policy decisions about water supply are made in this atmosphere of ambiguity and guesswork.

Stakeholders – decision-makers, users, administrators – no one has access to accurate, granular, reliable water data. How much water is being used, how much is wasted, who are the users, when do they use it and where is the highest need for water. None of this information is easily available.

Accurate, comprehensive, data-driven water management has the potential to change urban lives because non-revenue water is a problem at every scale – from individual buildings, to entire city networks. It has never been more important to understand our water and start generating high-quality water data.

According to a report from the UN, cities will be home to more than 2/3rds of the world’s population by 2050. Three countries will see the largest influx of people into urban areas – China, India, and Nigeria. Urban migration is usually accompanied by an increase in per capita consumption of water. This comes from lifestyle changes as well as economic activity.

Indian cities are going to see an accelerating increase in the demand for water.

At the same time, the Ministry of Jal Shakti anticipates a reduction in the availability of water. According to the Ministry, there was an estimated 1545 cubic meters of water available for each person in 2011. By 2031, they expect this to come down to 1367 cubic meters.

WEGoT Utility Solutions was created to provide excellent water data. Our founders grew up in cities that have repeated cycles of severe water shortages. From founders to ground staff – no one can miss the sight of water tankers on the road. But unlike other natural disasters, the water crisis gives us an unprecedented amount of lead time. We don’t have to wait for it to become an immediate threat. We can work right now, build greater efficiency into our systems and change consumer behaviour.

We can bring down the demand for water.

In the last 7 years, our flagship product, WEGoT aqua has saved more than 5 billion litres of water through a three-pronged approach – reliable measurement, accessible data, and useful analytics.

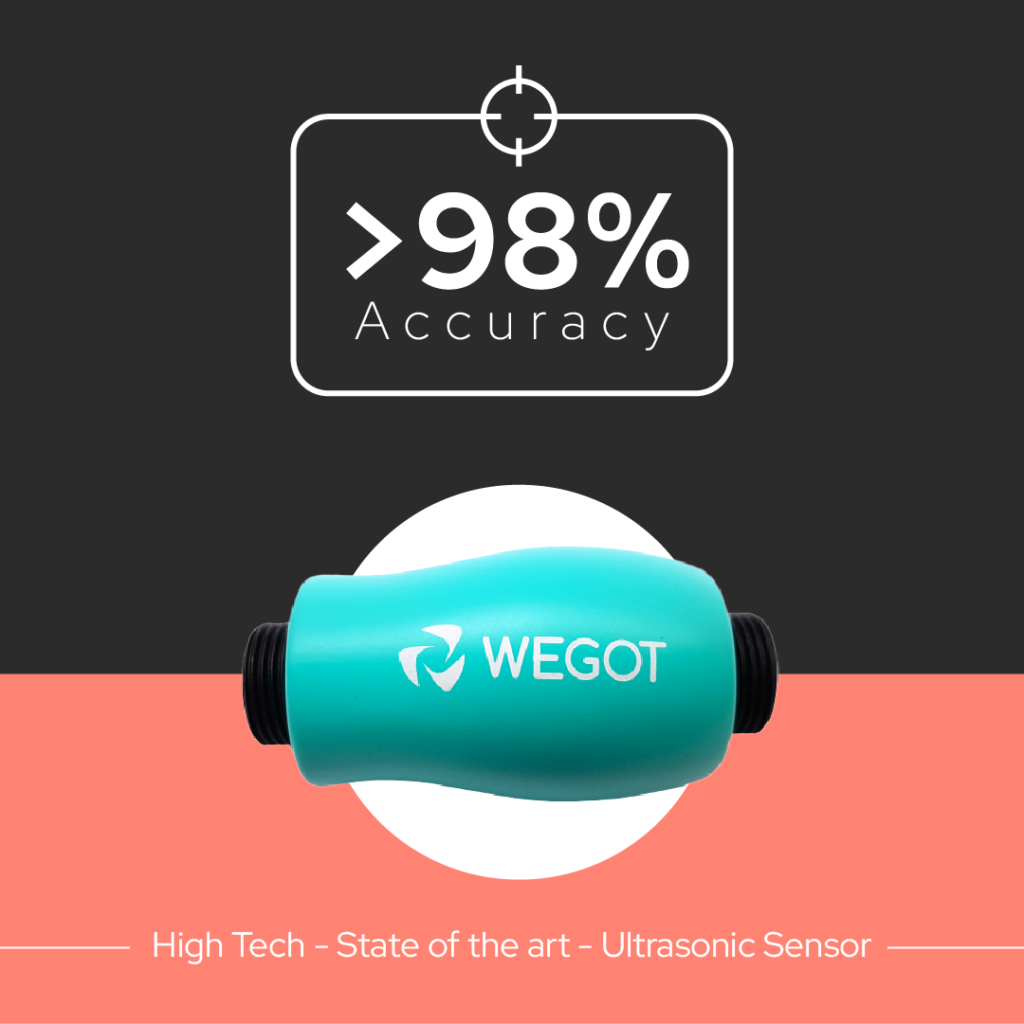

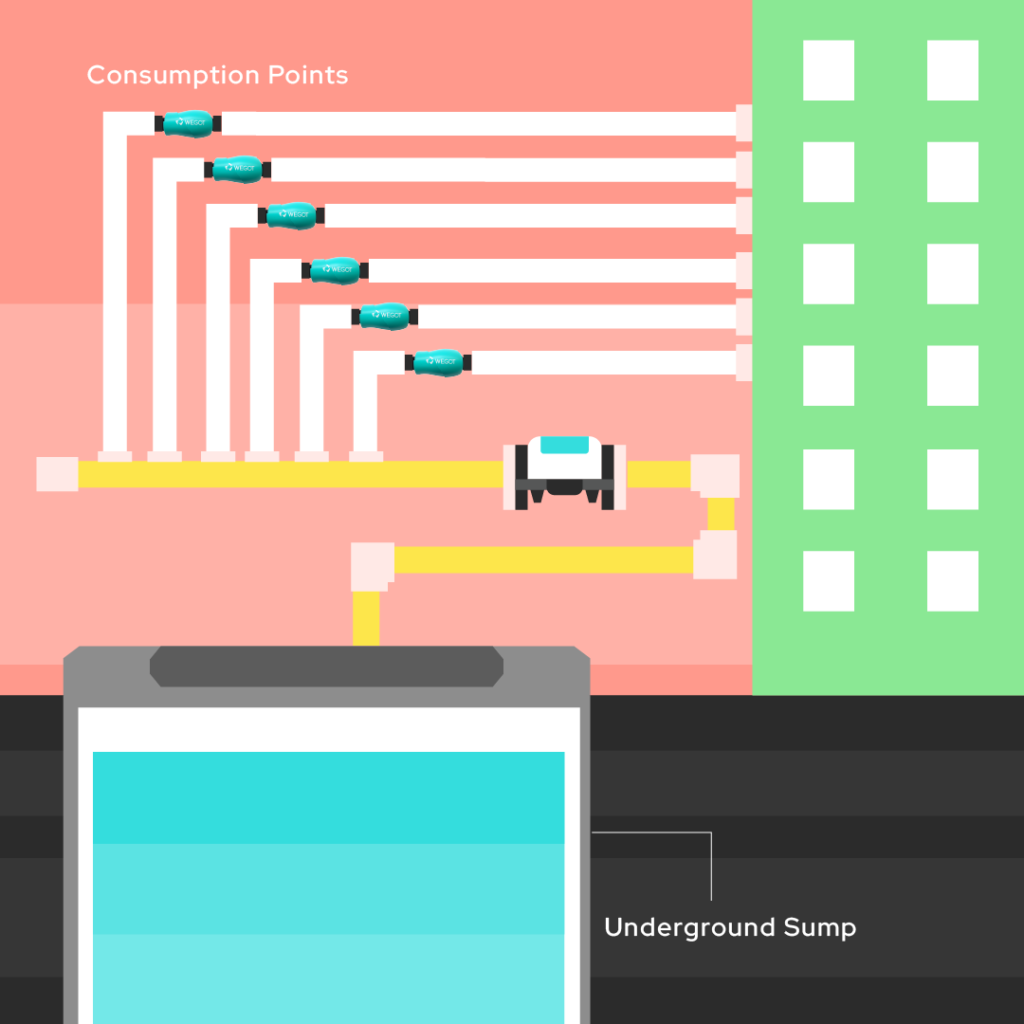

We monitor and measure water at both the source and consumption points. Our high-tech, state-of-the-art, ultrasonic sensor can measure water at >98% accuracy.

This sensor is easy to install in plumbing lines, and can be customised for varying pipe widths. This means that it can measure water flowing into an underground sump through a 100 mm pipe, and also be installed at every inlet to measure water at consumption points.

In the absence of such comprehensive measurement, many communities lose money every month to procure water. The management committee at Ceebros Boulevard, one of our residential clients, says that the WEGoT system has finally allowed them to recover the cost of procuring water by charging their residents according to usage.

The developer for Ceebros Boulevard had installed a sub-metering system for water. However, they were mechanical flowmeters that had to be read manually. These were not easy to access, so readings were taken only once in 6 months. If tenants or owners had changed during this period, there was a question about accountability for water usage and responsibility for the bills.

In contrast, WEGoT aqua’s sensors have no numbers on them. This was a deliberate design choice to reinforce the idea that there is no need for physical inspection of the device for collecting data. The sensors are IoT-enabled and communicate water data to the cloud. Data is delivered directly to mobile devices or desktop applications. Instead of inaccessible meters that are read infrequently, WEGoT aqua automatically updates water usage statistics throughout the day. Bills are generated automatically and every user is charged exactly for what they use.

End-to-end measurement and monitoring allows WEGoT aqua to quickly identify leaks – another major source of non-revenue water. Physical inspection for identifying leaks has many limitations. Some leaks are not even visible. “If water is leaking into a toilet bowl, how can you even tell?” asked one of our clients. WEGoT’s system monitors the health of the entire plumbing architecture. Therefore, it can send leakage alerts if there is continuous water usage at any inlet. In addition, we are able to deliver all water data, bills and alerts on mobile and desktop applications. During Covid lockdowns this allowed facility managers to monitor the health of the water infrastructure remotely.

A cloud-based water management solution also has the advantage of providing great analytics. WEGoT aqua’s app can help a resident answer detailed questions on water usage. They can see how much water was used in the kitchen the previous day, how much water was wasted in leakages this week, and even which time of day has the highest water usage.

Industrial plants, gated communities, or even entire cities, usually have insufficient money and manpower for maintenance and repairs. Automating water-related tasks allows a redirection of resources towards identifying weak spots in the infrastructure and reducing non-revenue water.

Gautam Lulla, Head – Facilities & Administration at the Murugappa Group, said that their technical team used to spend over one hour each day on water management. Now, they work on inspecting joints and bents for corrosion. “There is a lot more focus on preventive maintenance,” he says. “I can’t imagine going back to a manual system.”

Nikhil Anand, an environmental and urban anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania, has studied Mumbai’s water supply for over a decade. He says that cities must commit to maintenance because leaky systems are predisposed toward scarcity. We often work hard to find new sources of water. However, it is much better, in the long run, to care for existing infrastructure.

WEGoT wants to make this maintenance easy. We provide immediate incentives for water conservation. We are creating systems that bring down demand.

In our experience, WEGoT aqua’s rationalised billing, analytics, and leakage alerts bring down water demand by 30-50% in buildings. In the next 10 years, we expect to save 1 trillion litres of water.